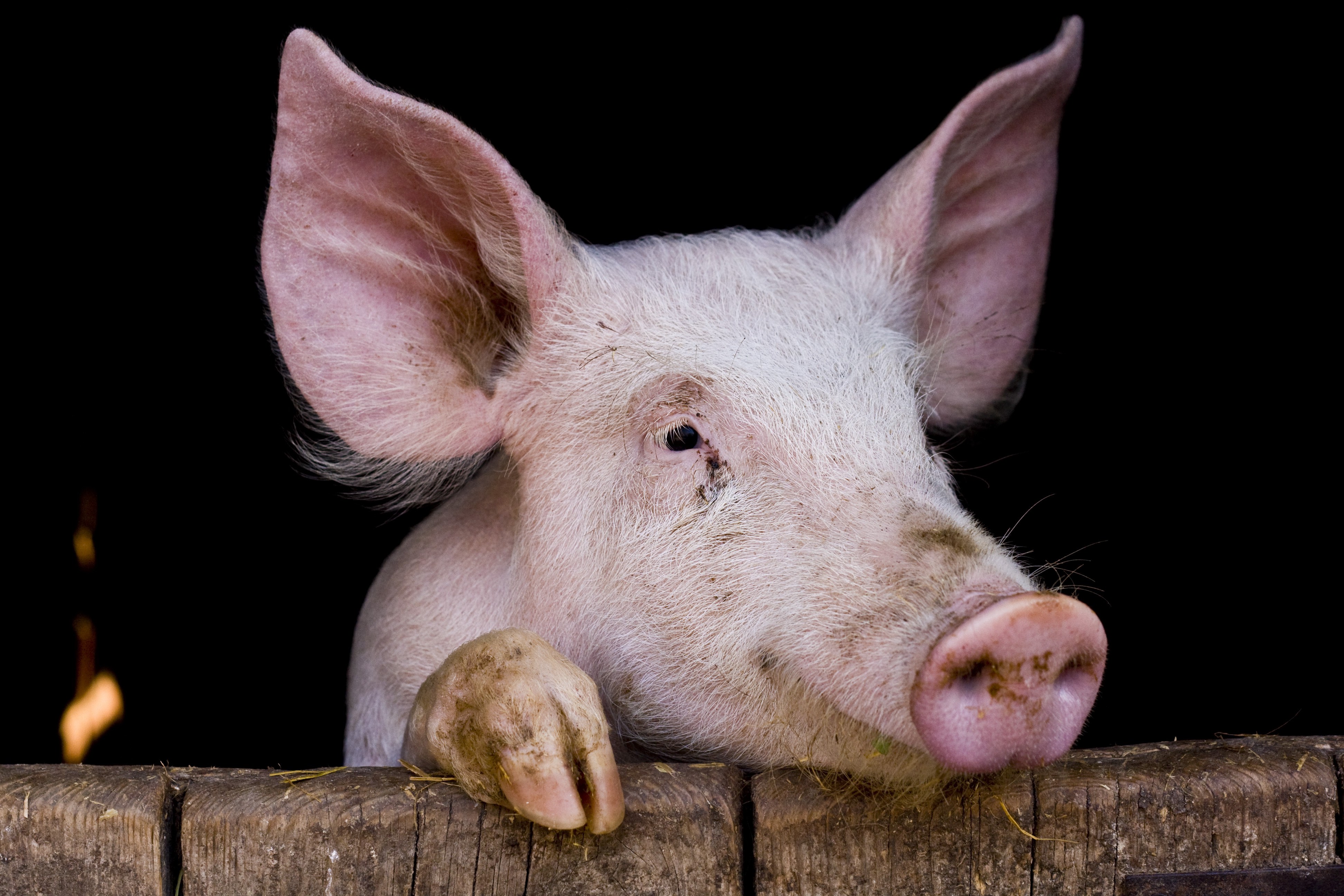

Last week, farmer Fergus Howie made headlines by calling for derogatory terms like ‘pigging out’, ‘fat pig’ and ‘porker’ to be banned from the Oxford English Dictionary, not because they insult humans but because they insult pigs, being inaccurate and misleading. Howie’s concern is economical: he worries that language like this creates the perception that pork is still a fatty meat and this will put people off buying it, when actually our modern pigs have been bred to be lean and muscular. Yet Howie’s campaign got me thinking about the broader consequences of our use of farmed animal names as insults.

In her podcast Animalogy, Colleen Patrick-Goudreau states that “we’re living in a time when we’re all called upon to be linguistically sensitive to vulnerable and disenfranchised groups”. We all need to be more mindful of our language when we talk about those who don’t look, emote or sound like we do, and that respect must also be accorded to nonhuman animals, perhaps the most vulnerable group of all (animals do not have the physiology to speak up for themselves). Because that’s what we do in civilised society, right? We respect the rights and integrity of those who are worse off than we are. Donald Broom, the world’s first Professor of Animal Welfare, states that “countries that treat animals well are regarded as civilised, and countries that don’t treat animals well feel guilty about not being civilised.”[i] Being ‘civilised’ matters.

But it’s not quite as simple as that. Joe Wills, lecturer in Animal Law, talks about the role of dignity in human rights discourse, stating that ‘dignity’ has historically been used to define humanity with reference to distinction from other beings (animals) that only have relative worth.[ii] Here we see the inherent contradiction within our obsession with being ‘civilised’ – on the one hand we want to appear civilised by providing high welfare standards for animals, but on the other hand the word ‘civilised’ is the word we use to distinguish ourselves from those same animals. Distancing ourselves from animals is fundamental to appearing civilised; that’s why we say that somebody with bad table manners is ‘eating like a pig’, or we describe a couple engaged in uncivilised or promiscuous sexual behaviour as ‘going at it like animals’. Remember that Bloodhound Gang song in the ‘90s? “You and me baby ain’t nothin’ but mammals; So let’s do it like they do on the Discovery Channel.”

Every time we use animal names as insults we subtly belittle the animal in question as inferior to us. The term ‘bird brain’, for instance, is a misguided insult: we now know that birds can do/understand things that even chimpanzees cannot, but this knowledge hasn’t been communicated from scientific behavioural research to public understanding. In Animalogy, Patrick-Goudreau shows how many words and expressions we use reflect a disturbing amount of disdain for animals and violence against them, both literally and linguistically i.e., ‘killing two birds with one stone’, ‘there’s more than one way to skin a cat’. Pejoratives like calling someone a snake in the grass, clumsy as an ox, crazy as a fox, a dirty rat, a filthy pig, a stupid cow, don’t necessarily reflect how we really feel about animals. And as Howie showed, they certainly don’t reflect the animals themselves. Patrick-Goudreau states that

When we talk about animals, we unconsciously participate in a system that belittles and commodifies them, minimises their suffering, unwittingly advocates violence against them, perpetuates cognitive dissonance and legitimises and conceals our institutionalised abuse of them.

Even the language we use to describe the human race versus animals is telling: we are ‘human beings’ while animals are never ‘animal beings’ or even nonhuman ‘beings’. It is as if animals are not ‘beings’ at all. Humans are one group, animals are generalised in another. Similarly, how we label different groups of animals impacts the level of respect and rights we give them. A ‘lab animal’ has different rights to a ‘pet’ even if they are both the same animal (a guinea pig, a beagle). We give a pet animal a name and thus acknowledge its personality. We deny other animals this by labelling them with numbers. Animals are not ‘farm animals’ – they are ‘farmed animals’: farming is something we do to them, not a part of their inherent nature. The labels we give our domesticated animals confuses this, and helps perpetrate the idea that cows, pigs, chickens and sheep are meant to be farmed, existing only for our benefit. Sadly, genetic selection means that today’s farmed animals are indeed creatures we have engineered to be ideally suited to food production, and they have physiologies and personalities that benefit productivity to the detriment of their welfare. But we have done this to them, and calling them ‘farm animals’ as if this is somehow integral to their nature justifies and excuses this.

Similarly, how we talk about the practice of eating animals is significant. ‘Carnism’, that is, the human practice of eating other animals’ flesh, remains unnamed so it appears a given, rather than a ‘belief system’ like veganism or vegetarianism. It is ‘normal’ to eat meat – so normal that it doesn’t need a name – whereas to refuse is to be part of a distinct outside group. The way we talk about animal flesh itself is also distancing. The Anglo-Saxons used the word ‘meat’ to mean simply ‘food’ – and called animal flesh exactly what it was: cow meat, pig flesh etc. However, when the conquering Normans entered Britain, they brought with them Old Norman language, which developed into Anglo-Norman. Many Norman and French loanwords entered our language, and these included words like ‘beef’ for cow, ‘pork’ for pig, ‘veal’ for calf. Meat ceased to be used in the biblical sense of ‘food’ (although we can still trace this in phrases like ‘coconut meat’) and now was applied only to animal flesh. Gradually, this ‘elevated’ language substituted the more literal Norse words. Even now, when we call flesh by the animal’s name, we remove the article or the plural i.e., ‘Lamb’ not ‘the lamb’, ‘I like eating chicken’ not ‘I like eating chickens’. We eat a ‘chicken leg’ not a ‘chicken’s leg’ – it no longer belongs to the chicken. A chicken wing is a KFC snack, not a bird’s arm. When we become more conscious of the language we use, the contradictions around the value we place on ‘natural’ foods become evident. We reject GM foods, yet we do not want our meat to look truly natural, as the connection to the animal would be harder to ignore.

Patrick-Goudreau does not just show the violence in the way we speak about animals – she also discusses how our vocabulary reflects how deeply connected we are to other animals and how integral they are to who we are as compassionate human beings. Many everyday words have animals hidden within, “reflecting how deeply rooted animals are within our consciousness and our history, our language and our hearts”. I keep returning to this as I read Pullman’s latest book in the His Dark Materials series, where a person’s dæmon is shorthand for the kind of person they are. Their very soul takes animal form, showing how integral animals are to us, expressing the core of our being. Yet the animals in Pullman’s books are never really more than projections of our human selves. If we are to become a truly civilised, compassionate society, we need to value animal beings as persons in their own right; we need to stop appropriating their names as human insults (‘fat pig’, ‘stupid cow’) and try to understand the authentic, individual natures of these complex animals. The language we use day-to-day is a subtle but fundamental part of this, so we need to be more mindful of what we say, and the consequences. And by thinking twice before we call someone fat or stupid, perhaps we’ll end up being kinder to one another too.

[i] Conference presentation at The Global Animal Education and Law Conference, University of Leicester Law Society, February 24, 2018 https://luls.org.uk/animalconference1

[ii] As above.