When it comes to the culling and hunting of wild animals, the public have significant power to adopt and amplify the conservationist point of view. This is evident in two current examples where citizens have passionately embraced the conservationist cause, with very different outcomes for animal welfare. Public support of extreme wildlife management in New Zealand, for instance, can be contrasted with public rejection of trophy hunting, specifically the recent threat by the Trump administration to relax the ban on importing ivory from elephants hunted in Africa. In New Zealand, the conservationist agenda is missing an essential ingredient, animal advocacy, the public caught up in the simple ‘thrill of the kill’. By contrast, the trophy hunting protests show animal advocates and conservationists working together and the public consequently embracing a cause motivated by compassion. Both examples demonstrate that our united public voice has real power to impact animal welfare. However, in only one case do we see genuine gains for both conservation and animal rights.

Conservation without compassion

In our finite ecosystems there is a strong argument for careful monitoring and ‘management’ of wildlife populations. Conservationists advocate the culling of invasive species to maintain biodiverse habitats: we need to choose which animals to kill ‘responsibly’ before nature does it for us, thereby maintaining endangered species[1]. This is a view shared by the majority of the population in New Zealand, where the government have set the goal of ridding the country of invasive predators by 2050. As many as 98% of New Zealanders agree with this policy[2]. There are also well-documented conservation reasons for hunting wild animals for sport. Last month the Trump administration announced plans to reverse an Obama-era ban on the importation of elephant trophies from Zimbabwe and Zambia, on the basis that legal, regulated sport hunting could benefit the conservation of the endangered species[3]. Income from trophy hunters provides incentives to local communities to conserve the game and generates revenue that can go back into conservation. Indeed, many hunters argue that ‘killing with kindness’ is not immoral if one respects the animal’s value as a sentient being[4].

It is difficult, however, to see anything respectful about having your photograph taken, smiling, next to an animal’s corpse, and of course such photographs are part of the prize for sport hunters. Researchers have shown that these hunters are more likely to demonstrate true ‘pleasure smiles’ when posing with prey: the bigger the kill, the bigger the smile[5]. It appears that many people really choose to hunt animals simply because they enjoy killing them. In New Zealand, citizens view ‘pest’ animals with what Bekoff calls “intense hatred”[6], children taking ‘stoat selfies’ in which they grin while holding up dead animals. Critics of New Zealand’s campaign have been threatened with actual physical violence by people who have come to hate these invasive creatures. Here we see the influence of a general population passionately united against wildlife ‘pests’, backing diverse organisations (including The Labour Party and the NZ Veterinary Association) in advocating 1080 poison, a devastatingly cruel method of animal destruction. A recent article by Helen Kopnina and colleagues rejects this type of ‘short-sighted’ conservation, which does not offer protection for animals judged ‘useless’ to human beings[7].

Compassionate conservation: the importance of animal advocacy

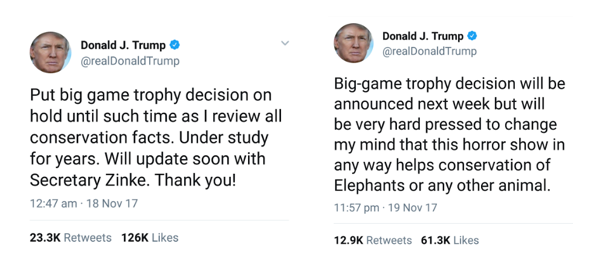

Conservationist Mary Pearl draws a clear line between people who are “really committed to wildlife conservation”[8] and animal rights advocates, who believe that every autonomous animal has the right to live. But need there be conflict? Animal advocates argue for humane alternatives to culling, such as encouraging or deterring animal movement with new food sources and other humane methods.[9] For example, increased advocacy on behalf of free-roaming cats (one of the top threats to US wildlife, killing billions of animals each year[10]) has resulted in an increase in the practice of trap-neuter-return (TNR) as a humane alternative to lethal management in the US[11]. It seems the US public are beginning to agree that ‘management’ need not mean killing, recent research documenting an increase in the popularity of large predators and a decrease in support for their lethal removal[12]. Certainly when the lives of charismatic mammals are at stake, we are far more likely to weigh in on the side of ‘compassionate conservation’ than lethal control. Recently there was mass public outcry on social media channels in response to the US ivory imports announcement, protesting that endangered elephant populations need our protection[13]. In Zimbabwe and Zambia (two of the three most corrupt countries in the world according to Transparency International), bribery and corruption undermine the regulation of poaching. The Wildlife Department of the Humane Society International explains that “corrupt officials allow animals to be killed in dangerously high numbers – to the point of harming the conservation of the species”[14]. Whether motivated by this knowledge or by simple disgust at the destruction of these ‘majestic’ animals, the public made their opposition clear in a united call for a compassionate conservation paradigm.[15] Chris Darimont recently wrote of the Canadian ban on grizzly bear hunting: “how society ought to act is ultimately decided by values. The hunting ban aligns with most of society’s moral compass: trophy hunting of inedible animals is no longer acceptable”[16].

Better together: the power of united voices

The apparent reversal of Trump’s decision shown in these Tweets was in direct response to “public outrage”[17] via social media. On December 22, 2017 the US Court of Appeals for the DC Circuit upheld the conservation mandate of the Endangered Species Act, supporting the need to rigorously analyse applications to import hunting trophies of species threatened with extinction. The Court also held that the agency must take public comment on any blanket decisions to allow or prohibit trophy imports based on individual countries management plans. This brings hope that public opinion can influence policy and shows the potential power of dissent when conservationists and animal lovers – as opposed to New Zealand’s animal ‘haters’ – unite in protest. Katherine Richardson, leader of the Sustainability Science Centre, asserts that animal rights advocates and conservationists have real power to “exploit the synergy that we have and raise our voices together”[18]. The situation in New Zealand shows the destructive consequences of a conservationist agenda uniting the public in passion against wildlife ‘pests’. Yet trophy hunting protests demonstrate the constructive power of compassionate conservation, amplified by public support of animal rights. The strength of public opinion displayed here supports the idea that state wildlife agencies need to broaden their constituents to include the general public in their decision-making if it is to reflect genuine societal desires.[19]

Kopnina advocates ‘ecocentric conservation’ whereby conservation of one species does not come at the expense of a host of other ‘lesser’ animals. This is very much in line with the compassionate conservation proposed here, whereby recognising the intrinsic value of both human and animal nature “and the need for the entwining of eco-justice and social justice” offers a path to a just world. In 2017, 96 per cent of animal life consists of humans and domesticated animals, leaving only four per cent wildlife[20]. If we are to achieve justice for that four per cent, conservationists and animal rights advocates need to work together to come up with practical, values-based, compassionate solutions that the public can get behind, whatever the species.

References

[1] Pearl, M. (2014). Killing Wildlife: The Pros and Cons of Culling Animals. In: James, W. (ed.). National Geographic.

[2] Bekoff, M. (2017). Does Everybody Really Hate Possums? The Bandwagon Effect. Psychology Today.

[3] D’Angelo, C. (2017). Trump to Lift Ban on Import of Elephant Trophies from 2 African Nations. Huffington Post, 16 November 2017.

[4] Federated Farmers national president Katie Milne defended school possum hunt fundraisers in New Zealand, so long as they are carried out ‘ethically’: “We do have to treat all animals with respect and make sure they’re doing it in the correct way, so that it does offer the greatest amount of respect for the animal they’re putting down” (US professor condemns New Zealand’s pest and possum ‘murder’. Newshub, 23 November 2017).

[5] Child, K. & Darimont, C. (2015). Hunting for trophies: Online hunting photographs reveal achievement satisfaction with large and dangerous prey. Human Dimensions of Wildlife, 20, 531-541.

[6] Bekoff, M. (2017), as above.

[7] Kopnina, H., Washington, H., Gray, J. and Taylor, B. (2018). The ‘future of conservation’ debate: Defending ecocentrism and the Nature Needs Half movement. Biological Conservation, 217, 140-148.

[8] Pearl, M. (2014), as above.

[9] AnimalAid. (2017). Available at: https://www.animalaid.org.uk/the-issues/our-campaigns/wildlife/alternatives-culling-factfiles/ [Accessed 29 September 2017].

[10] In 1993, a US Congressional report “Harmful Non-Indigenous Species in the United States” named feral dogs and cats as “two of the three most common subjects of wildlife control efforts” of US national parks and wildlife reserves.

[11] Spehar, D. D. and Wolf, P. J. (2017). An Examination of an Iconic Trap-Neuter-Return Program: The Newburyport, Massachusetts Case Study. Animals, 7, 81.

[12] Jackman, J. L. and Way, J. G. (2017). Once I found out: Awareness of and attitudes toward coyote hunting policies in Massachusetts. Human Dimensions of Wildlife, 1-9.

[13] According to the 2016 Great Elephant Census, the number of Savanna elephants dropped by 30% between 2007 and 2014.

[14] Telecky, T. M. (2014). Hunting Is a Setback to Wildlife Conservation. Earth Island Journal.

[15] Jackman, J. L. and Way, J. G. (2017), as above.

[16] Darimont, C. (2017). Trophy hunting: Science on its own can’t dictate policy. Nature, 551, 565.

[17] The Center for Biological Diversity stated that “public outrage has forced Trump to reconsider this despicable decision”.

[18] Richardson, K. (2017). Keynote: Livestock and the boundaries of our planet. Extinction and Livestock Conference. London, UK.

[19] An example where this is currently not happening is in South Africa, where the Department of Environmental Affairs set up a Consultative Wildlife Forum as a way to ‘engage with private entities about wildlife policy’ (Snijders, D. 2014. Wildlife policy matters: inclusion and exclusion by means of organisational and discursive boundaries. Journal of Contemporary African Studies, 32, 173-189). This forum actually provides a platform for hunters and other with vested wildlife consumptive interests to shape government policy, excluding NGOs and representatives from labour and environmental organisations. Snijders reveals that “at industry meetings, direct strategies to limit ‘greenies’ access to the institutional field are discussed along with tactics to weaken their legitimacy.”

[20] Juniper, T. (2017). What’s really happening to our planet? Extinction and Livestock Conference. London, UK.

It looks like you’ve misspelled the word “Draven” on your website. I thought you would like to know :). Silly mistakes can ruin your site’s credibility. I’ve used a tool called SpellScan.com in the past to keep mistakes off of my website.

-Rebecca

It’s actually the name of a monkey at the sanctuary: it’s spelled correctly