As part of my MSc in Animal Welfare, last week we were asked to discuss Roger Scruton’s essay Eating our Friends. In this piece Scruton argues that those who care about animals have “a duty” to eat meat because “Where there are conscientious carnivores… there is a motive to raise animals kindly”:

“If meat-eating should ever become confined to those who do not care about animal suffering then compassionate farming would cease. All animals would be kept in battery conditions, and the righteous vegetarians would exert no economic pressure on farmers to change their ways.”

The idea that we have a duty to eat our friends sounds insane, but there’s something in Scruton’s argument when we focus on the possibility of short-term change in the farming industry. Actually, it’s a debate that came up following a Universities Federation for Animal Welfare conference earlier this summer. As with recent conferences held by Compassion in World Farming and the British Ecological Society, I’d expected the catering to be animal-free, yet there were no vegan options served during the breaks, there were mainly meat dishes at lunch, and most of the vegetarian options contained egg or dairy. None of the meat-based food had any accompanying information on the provenance of the animal ingredients. When the organisers asked for feedback, I suggested that it would have been nice to see a more plant-based menu and, where meat, eggs and dairy were served, some detail provided on their origin. It was particularly discomforting to watch a grim presentation on the abuses broiler chickens suffer when being caught for slaughter, and then a hour later to see chicken on the lunch table. The organisers’ response was that the catering was 70 percent vegetarian/vegan but they were reluctant to go further at the next meeting because:

“those who work on improving farm animal welfare are proud of the work they do and many choose to support the industry and investment in improving welfare by eating meat. Indeed at the conferences run by our sister charity the Humane Slaughter Association the dietary requests are usually to ensure that there is are sufficient meat options e.g., poultry, beef, pork on the menu for the area of the industry they work in.”

This drives home the gap between animal welfare and animal rights. I’ve always believed/hoped that it’s possible to support both: improving animal welfare being a step towards eventual animal liberation. As Corine Pelluchon says in her chapter in Ethical Vegetarianism and Veganism,

“Because we live in a speciesist and pluralistic society, it is impossible to immediately eliminate animal exploitation. The process may take time and be gradual… The point is to promote a society in which it becomes easier to live well with less suffering for animals” (Linzey and Linzey, 2018: 45).

But what if to reduce suffering you have to buy into a system that treats animals as edible commodities? Doesn’t funding ‘humane’ farming mean compromising one’s belief that there’s no such thing as humane slaughter? If we recognise industrial animal farming as the breeding, enslavement and slaughter of sentient beings for our own use, the concept of attempting to reform or improve conditions seems absurd. Imagine suggesting that human slavery just needed to be reformed, with slaves treated better (Patricia McEachern makes this point in her chapter in the same book (Linzey and Linzey, 2018:159)). This is a concern often raised among animal rights activists and it came up recently around Prop 12, legislation that will give farmed animals in California more space and (slightly) better lives. Some opposed Prop 12 on the grounds that giving animals bigger cages merely reduces the impetus for people to push harder for bigger reform i.e., total abolition of animal ag. I get it, but at the same time if an animal is suffering and you have the chance to ease that suffering, even marginally, I don’t see how anybody could choose not to do that. Especially for the sake of an ideal that still seems extremely remote.

Christine Korsgaard describes my personal feelings about consuming animal products more eloquently than I ever could in her recent book Fellow Creatures:

“The question is not just about numbers and consequences. It is about you and a particular animal, an individual creature with a life of her own, a creature for whom things can be good or bad. It is about how you are related to that particular creature when you eat her, or use products that have been extracted from her in ways that are incompatible with her good.” (Korsgaard, 2018: 223)

When we eat animals, we subjugate their basic rights for our own temporary pleasure. We wouldn’t do this to other humans, so it feels inherently wrong to me to do it to other species. After all, even when we’re talking about a happy pasture-fed cow, eating her flesh is not going to be compatible with her good. I suppose in this respect I take a virtue ethics approach, focusing on enacting my own personal moral values rather than getting bogged down in broader rights and duties. Still, I don’t know how practical this is when it comes to reducing animal suffering in the short term.

What if we can extract products from animals without compromising their wellbeing? Scruton’s argument (and UFAW’s) does resonate when we consider the advent of slaughter-free ‘clean meat’, grown in a laboratory. Some vegans reject cultured meat because the concept still treats animals as “food not friends”. But clean meat isn’t for vegans: it’s a compromise for meat eaters, for conscientious carnivores who aren’t willing to give up the taste of meat but want animals to be treated well. I think clean meat could provide the solution to the debate above, offering the meat industry a new, more ethical path (we’re already seeing meat producers like Tyson investing in this new protein). I’d certainly feel far more comfortable supporting an industry where the animal is not only “raised kindly” but he or she doesn’t have to die to produce meat for our plates.

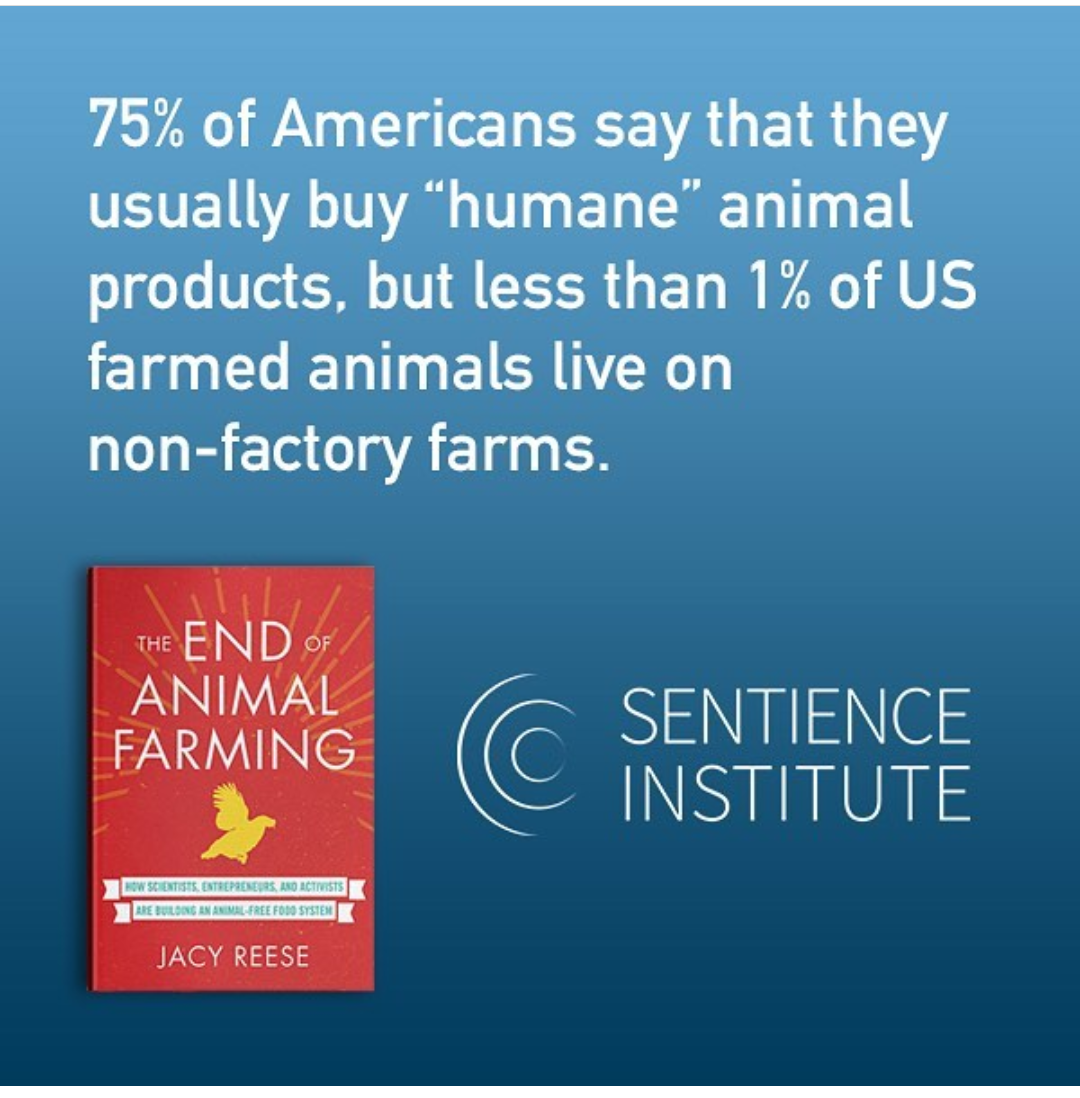

Without clean meat, I think Scruton is living in a fantasy land: to imagine that everybody will eventually listen to “conscientious carnivores” and decide to choose organic high-welfare meat is unrealistic. These options have been available for a long time and most people (whether or not they claim otherwise) don’t choose them, whether because of financial constraints, lack of education, confusing labelling, or time economy. Sadly, the existence of humane meat all too often gives meat-eaters an excuse not to change their fundamental behaviour. If everybody who told me “I only buy organic meat” really only bought organic meat, my local KFC would have gone out of business!

Furthermore, it might be argued that no farming system is truly entirely ‘high welfare.’ Even in organic systems, especially in the US but also here in England, standard husbandry practices like separating and slaughtering male dairy calves, destruction of male chicks, painful branding or tagging, castration, beak trimming and so on etc still occur. And all these animals, factory farmed or not, end up in the same place: walking, terrified, to slaughter.

I don’t believe that taking the life of an animal who doesn’t want to die is okay, no matter how comfortable that life might have been. But equally, we’re not at the stage where abolition of animal farming and meat eating is remotely realistic, so welfare reform must be better than nothing. And yes, I do see that we can’t refuse to give money to farmers and still expect them to invest in welfare. Is there some way to support welfare improvements without having to buy meat and dairy? Donating to an organisation like Compassion in World Farming might be one option. Better still, we can educate our friends and family who already eat meat on how to buy genuinely ethically sourced produce; to look out for Soil Association labelling and to invest in local organic farms where the producers genuinely care about their animals’ welfare. We live in a world where most people still eat animals but are open to making more conscientious decisions about the kind of meat they consume. Rather than attacking those people, why not help them make the best choices? Surely that would have a much more positive impact on animal welfare than alienating ‘conscientious carnivores’ altogether.